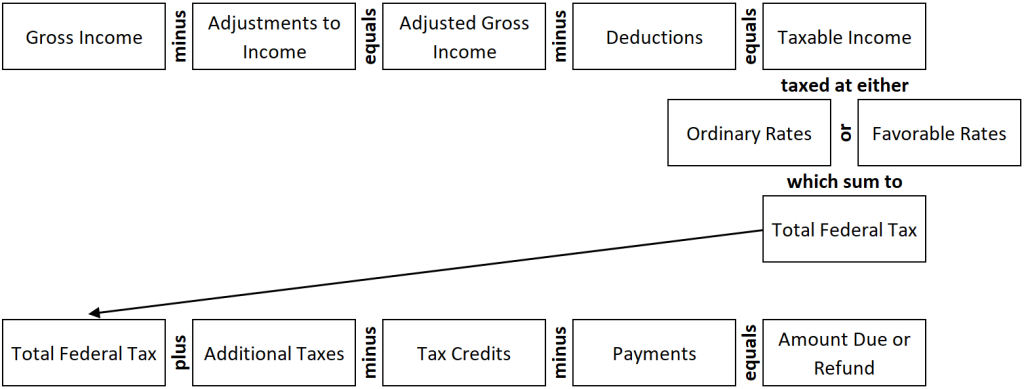

Introduction. Self-employment income reported on a tax return is increasingly common, and for tax year 2020, 28.4 million returns were filed with a Schedule C attached. The IRS says,

“An activity qualifies as a business if your primary purpose for engaging in the activity is for income or profit and you are involved in the activity with continuity and regularity. For example, a sporadic activity, a not-for-profit activity, or a hobby does not qualify as a business” (underlines added for emphasis).

Schedule C is thus titled “Profit or Loss From Business,” and would be used whether you are a sole proprietor, or have incorporated as a limited liability company (LLC), and didn’t elect to be taxed in a different way. Due to how self-employment income on Schedule C is taxed (it’s pretty brutal), tracking all of your expenses is critical to avoid an unnecessarily high tax bill.

Joint venture with your spouse. Most often, self-employed income is in the name of either the taxpayer or the spouse. But sometimes, both taxpayer and spouse may run a business together. Per the IRS,

“Generally, if you and your spouse jointly own and operate a… business and share in the profits and losses, you are partners in a partnership, whether or not you have a formal partnership agreement. You generally have to file Form 1065 instead of Schedule C for your joint business activity…”

That is problematic due to the complexities of filing Form 1065—refer to My buddy and I formed a business together. What do we need to watch for? for more information. However, this can be avoided if both of the following stipulations are met:

- You and your spouse wholly own the unincorporated business as community property and treat the business as a sole proprietorship (and not an LLC); and

- You and your spouse elect to be treated as a “qualified joint venture,” which means:

- Each person materially participates in the business; and

- You are the only owners of the business; and

- You file a joint tax return for the tax year.

Joint venture with someone other than your spouse. If your business includes anyone other than just you, or you and a spouse, you won’t use Schedule C to report the income or loss and it will be taxed as a partnership, unless the partnership elects to be taxed as an S-Corporation.

Ownership of the income matters. Special attention is paid by the IRS to whose income is being recorded on a Schedule C. We don’t see this kind of attention paid on retirement income or investment income. This nuance is due to the fact that the self-employment tax (SE tax) is 15.30% of net business income, comprised of the following four pieces:

- 20% for the employee’s share of the Social Security tax;

- 20% matched by the employer for the Social Security tax;

- 45% for the employee’s share of the Medicare tax;

- 45% matched by the employer for the Medicare tax.

So like wages on a W-2, business income recorded on Schedule C requires payments into both Social Security and Medicare. And since a self-employed person is both the employee and employer, they are paying both sides. A retiree’s Social Security benefit is determined in part by the amount of Social Security tax paid in over the course of an individual’s career—both the employee themselves via tax withholding, and their employer’s share via payroll taxes. Hence, the IRS pays close attention to who should get credit for the self-employment tax paid as a result of Schedule C business activity.

Income. This is alternatively referred to as simply “income,” or “gross receipts,” or “revenue,” etc. It refers to money received from the customers of your self-employment activities and does not include any personal money which you put into the business. This is sometimes reported to you on a Form 1099-NEC from the company who paid you. NEC stands for “non-employee compensation.” Previously this was Form 1099-MISC, but in 2020, the IRS split out the two forms (the 1099-MISC still exists but is not used for these payments). If a company who wants to pay you previously asked you to fill out a Form W-9, that’s what it is for. Filling out a W-9 will generally result in you receiving a Form 1099-NEC.

Think of Form 1099-NEC as being the company tattling on you to the IRS. But it’s not by choice—if you pay an individual $600 for goods or services during any given tax year, you are required to tattle on them to the IRS by submitting a 1099-NEC—and if you don’t, the non-tattling company may be fined between $50-$280 for forms not submitted. Additionally, this year’s companies like PayPal and Square will be sending out Forms 1099-K if transactions in (not out) totaled more than $600 during the year. Of course, not all companies will send out these required forms, and individual taxpayers almost never send them—but regardless of whether you receive a 1099-NEC, all business revenue from all sources is required to be reported on this schedule.

Cost of goods sold (COGS). Some companies would like to track their operating margin and gross profit before expenses. This allows for the matching principle of accounting to be effective. The IRS doesn’t have a preference for how you track these expenses, but they do require you to be consistent. If you would like to track COGS rather than expense your COGS as a business expense, use Parts I and III of the Schedule C. This method is not recommended for service entities or very small entities, but is generally recommended for retail or manufacturing entities. The calculation for COGS is as follows:

- Inventory at the beginning of year; plus

- Purchases, cost of labor, materials and supplies and other costs; less

- Inventory at the end of the year.

For example, if you are a bookseller and start the year with an inventory of $10,000 (your cost), spend $100,000 buying books from wholesalers over the course of the year, and end the year with an inventory of $20,000 (your cost), your COGS would be $90,000. If instead you expensed materials and supplies as you purchased them, the deduction would be $100,000. But your profit margins wouldn’t make a lot of sense and running your business may be more difficult over time.

Business Expenses. Alternatively referred to as “business deductions,” these would be costs which the IRS considers “ordinary and necessary” to running your business. The Agency is less concerned with the categorization of the expenses than they are with the expenses being valid and directly allocable to your business. While we don’t require full documentation to enter a Schedule C, in a tax audit, the IRS would require you to substantiate all business expenses. Failure to do so could result in the agency disallowing those expenses. Documentation is generally comprised of receipts and invoices, but in some cases, could be a handwritten log of expenses and proof of payment.

For more information on business expenses, please refer to What are the common Schedule C expenses?

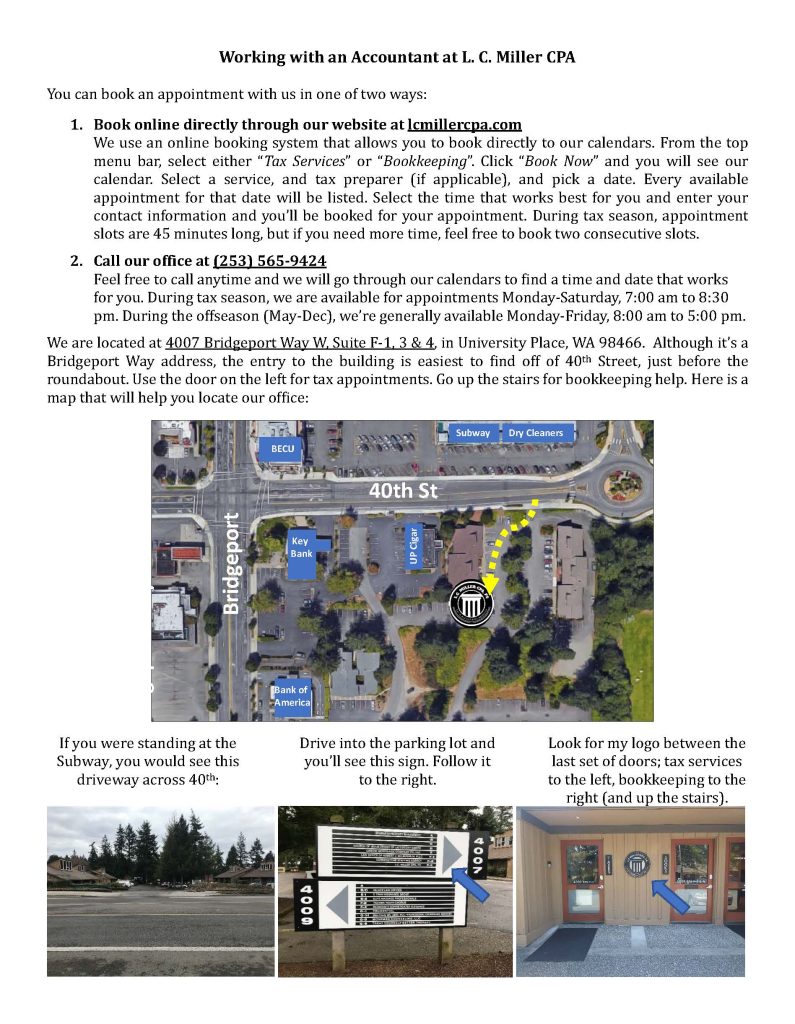

Bookkeeping services are available. If you would like to consult with a member of our bookkeeping team to see if we can be of assistance in tracking your business income and expenses, please visit our website at: www.lcmillercpa.com/bookkeeping and click on the “Book Now” button. This will allow you access to the calendars of our bookkeeping team where you can set up a free consultation. Our bookkeeping team is designed to help as much—or as little—as you would like, and can work within every budget.

For additional information, please visit the source(s) for this article:

www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i1040sc.pdf